Fake news, real women: Disinformation gone macho

When disinformation is weaponized against women, misogyny rears its ugly head

%

%

%

%

%

%

%

%

MANILA – The screenshot is hazy but in a sea of comments it stands out. In it is a woman wearing nothing but glasses and straddling a naked man. It is as crude as it gets, but it is just one of the weapons used against Philippine Senator Leila de Lima, who is among President Rodrigo Duterte’s harshest critics.

It has never been properly established that it is De Lima in the screenshot or the video from which it was supposedly taken. But this has not mattered in the court of public opinion. As far as Facebook comments are concerned after the image went viral, De Lima is an immoral woman, and therefore has no credibility. So she has been detained; she deserves to be behind bars, and that’s that.

The Philippines placed 10th in the Global Gender Gap report in 2017, making it the most gender-equal country in Asia. It is far ahead its neighbors, with the closest being Lao PDR and Singapore at 64th and 65th place, respectively. But the indices, which measure gaps in educational attainment, political empowerment, and health and survival, merely look at quantifiable data such as seats in parliament, literacy rates, and participation in the labor force.

Here in the Philippines, they have failed to capture the country’s long history of misogyny, which has now found a new breeding ground: online.

“In the past few years, we’ve found that it’s even more difficult to be a woman – and a woman in power,” said Vice President Leonor "Leni" Robredo.

“Women leaders have always had to prove themselves more than their male counterparts. These days, however, we are more vulnerable to personal attacks on a public sphere, because we have officials who openly, and casually, drop these rumors and allegations against us. These attacks spread like wildfire, given the rise of social media and an organized disinformation drive.”

Like De Lima, Robredo has been the target of such attacks. The widow of the late secretary of the interior and local government Jesse Robredo, she has been subjected to speculations about her private life, including rumors of an affair and, at one point, even pregnancy.

In a country where 64% out of a population of 105 million are active on social media, these speculations have spread fast and wide – and continue to linger even without any apparent basis.

Genderized disinformation

Disinformation is one of many in the arsenal of weapons used by trolls and propaganda networks to attack and discredit opponents. It can take several forms, such as fabricated headlines, misleading captions, or falsified information. Female targets of disinformation, however, often face direct attacks on their identity as women.

In the Philippines, observers say that these kinds of attacks against women became more noticeable after the election of President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016. The non-governmental organization Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA), for one, says that after the presidential polls two years ago, harassment, especially of women journalists and politicians, became commonplace.

“Male journalists are also harassed online, they also get cussed out,” said FMA executive director Liza Garcia.

“They also get that, they also get death threats. But when it’s a female journalist, it centers on their being a woman, on their bodies, like, ‘you’re so ugly, but I still hope you get raped.’ So what does that have to do with your being a journalist? It has something to do already with your being a woman. They would say, ‘You’re a whore,’ things like that.”

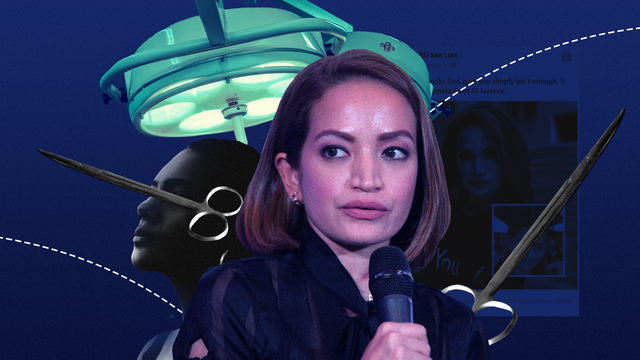

It’s an unpleasant experience that Al-Jazeera correspondent Jamela Alindogan has gotten used to after years of being a journalist based in Manila. She has ignored a bulk of the harassment, but in late 2016, she felt the need to draw the line.

In August that year, Alindogan had shared on Facebook another network’s report on the deaths of soldiers while fighting the armed group Abu Sayyaf. But her comment that accompanied the video somehow earned the ire of several Duterte supporters. They would become even more upset two months later, when Alindogan interviewed the President on camera and asked him questions regarding his stance on democratic processes and the atrocities of the Marcos regime.

Soon after, Alindogan noticed a strange kind of disinformation campaign aimed at her. This time around, she did not let it pass.

“It was one of the rare times that I spoke out publicly,” recalled Alindogan. “I called it out online, both Facebook and Twitter. Not just because of me but the other woman accused of being me, pre-surgery. She did not deserve that. It was ridiculous and infuriating.”

‘It’ happened to be comments and stories posted online of Alindogan supposedly having undergone plastic surgery. A meme, which circulated on Facebook, had her photo and that of another journalist posted side by side with the caption, “When the looks God gave you simply isn’t (sic) enough. It pays to be Jamela from Al Jazeera,” implying that Alindogan had work done on her face.

Low blows and questionable assumptions

“If they can’t attack you for the work that you do, they attack how you look because they expect that our looks make up who we are as women.”

Alindogan believes that blows to a woman’s personal life and appearance are cheap shots aimed at destroying her credibility. At the same time, they carry questionable premises, such as what matters to women and how they should behave.

Said Alindogan: “If they can’t attack you for the work that you do, they attack how you look because they expect that our looks make up who we are as women.”

She said that these attacks place an unfair burden on women that aren’t placed on men.

“I think women are vulnerable to all sorts of rumors but often they are vilified for their physical appearances and their personal lives,” Alindogan said.

“Men often always get a free pass for being separated or divorced or womanizing. Not women – those who do not live up to society’s unreasonable demands of social norms are vilified as witches. It’s as if not being able to fit the mood makes you ill-equipped to do the work at hand.”

Robredo has observed the same pattern, saying, “The goal in these smear campaigns is to discredit, but often we find that male politicians are attacked less personally than their female colleagues. Women in politics are constant targets of sexual harassment, moral attacks, and criticisms against their families. Their track records, no matter how stellar, are more easily overshadowed by allegations of such kind. If a male official is accused of an affair, would it have as much effect as when the same allegations are made against a female official? We have seen that it does not, and men are even free to flaunt about such.”

“Most of the things that have been said about me are attacks against me as a woman,” said Robredo, who tends to speak in a calm, even tone. “From how my knees look, to being called someone’s mistress, to what I wear. They work on cultivating a perception that I am a ‘weaker’ leader simply because I am not a man – more so a tough-talking one.”

Misogyny from the top?

"In the past few years, we’ve found that it’s even more difficult to be a woman – and a woman in power. Women leaders have always had to prove themselves more than their male counterparts."

The President has been known to crack sexist jokes and has made light of matters such as rape. He has even made lewd comments about Robredo, who belongs to the opposition party and who he kicked out of the Cabinet sometime ago. While on an official visit to South Korea, he solicited a kiss on the lips from a Filipino female fan.

The President and his supporters have said that all these have been all in good fun, but many Filipino women aren’t laughing. Garcia is among those who say that the President’s careless behavior and use of language may be sending the wrong message to men and even boys.

She argued, “Because you have a president who is a sexist, misogynist, and if you have a president who says rape jokes, who can say those things, when he’s supposed to be a leader, a role model for everyone, especially for boys, young men, and if he says that's okay to shoot women combatants in the vagina or it's okay to rape women – perhaps that is also the attitude that other young men might start emulating.”

To UP sociologist John Andrew Evangelista, it is only right that Duterte be held accountable for his rhetoric against women. But he said that the President is just a symptom of an even bigger problem.

“I wouldn't say that he's the cause of it, but he revealed an already brewing misogyny underneath our culture,” said Evangelista. “He just put it out there. And because he revealed it and that’s how he talks on his platform, the platform of the presidency, I'm not surprised that there are people willing to also take that same language.”

“We can always argue that Duterte is shaped by the misogynist culture,” he continued. “Let's hold him accountable but let's also keep in mind that there's a culture that allowed for a Duterte to happen. And that’s the bigger struggle: how do we dismantle that culture?”

Disinformation most damning

There is no doubt, however, that the kind of disinformation aimed at the likes of Robredo, Alindogan, and De Lima had a far more serious purpose. It can even be argued that in the case of De Lima, the disinformation campaign against her helped put her in detention.

The senator is currently being held at the police Custodial Center in Quezon City after the Duterte administration filed a case of drug-trafficking – a non-bailable offense – against her. But long before she was arrested, she had already been forced to endure a lynching online. The now-infamous video and its screenshots, supposedly showing the senator and her then driver-lover, were everywhere on Facebook, from the comments to posts on several pages and groups.

In 2014, during De Lima’s congressional confirmation hearing as justice secretary, rumors about such a video were already floating around. But a different president was at Malacanang Palace at the time, and the lawmakers on the Commission on Appointments apparently saw no point in considering it during her hearing, saying it was all still hearsay.

It took two more years and another president before the video and the screenshots became viral online. But it wasn’t just the online comments section that proved vicious. At the House of Representatives, an official probe supposedly on the drug-trafficking charges against De Lima dragged out even the most private details about the senator’s relationship with her driver.

Then-speaker Pantaleon Alvarez, who has admitted to having a mistress, even said that there was no problem with showing the video during the hearing, while President Duterte himself joked about showing the scandalous video to the Pope.

As De Lima sees it, the accusations made against her, especially those speculating about her personal life, were fuel to the fire. She said, “There were accusations against me that were deemed shameful and politically ruinous because I am a woman, but, at the same time, are the very same things that are seen as acceptable – and even impressive – when attributed to a man.”

“My track record as a straight-shooting, action-oriented public servant, who fears and favors no one, speaks for itself,” said De Lima, who has long been separated from her husband.

“For that reason, I believe that outrightly accusing me of corruption or involvement in illegal-drug trading would not have gained any traction were it not for the tactic of first conditioning the public to condemn me for circumstances that are deemed unacceptable for a woman. Hence, the slut-shaming paved the way for the other false accusations.”

Female foes for the President

“There were accusations against me that were deemed shameful and politically ruinous because I am a woman, but, at the same time, are the very same things that are seen as acceptable – and even impressive – when attributed to a man.”

De Lima had first encountered Duterte when he was still mayor of Davao City in the country’s south and she was chief of the Commission on Human Rights. She had gone to Davao to investigate allegations that a death squad, at the behest of the mayor, was responsible for a rash of extrajudicial killings there.

Seven years later, as head of the Senate justice and human rights committee, De Lima would open public hearings on the extrajudicial killings being committed supposedly as part of Duterte’s drug war.

She now believes that a woman speaking up against the President was a blow to his ego, hence the vicious nature of the attacks against her.

“If I were male, Duterte’s ego would not have been so offended by being called out by me,” De Lima said. “He really does not like to be criticized by women. So I think, if I were male, the reaction to my criticism would not have been so violent, malicious, and scandalous.”

She said that feminism in the country has a long way to go, especially in the current political climate.

“Feminism in the Philippines still has a lot of battles to fight,” she added. “And with a President who is anti-women’s and anti-human rights, this is the greatest challenge now facing the Philippine women’s movement. As I have said before, the fight against Duterte’s authoritarian rule will be a battle that will be primarily fought by women, because they are his foremost victims.”

Some women are already fighting back. Zena Bernardo, a development worker and member of #BabaeAko (I Am Woman) movement, said of Duterte: “He keeps picking on women so we just said, ‘I am a woman, what’s your problem?”

The movement, in fact, was born in May 2018, after the President said that the next Ombusdman should not be a woman. It launched a social media campaign series of videos of women vowing, “Lalaban ako (I will fight),” which helped it earn a spot on Time magazine’s ’25 Most Influential People on the Internet’ for 2018.

Women speak up

Bernardo said that social media proved instrumental in the movement gaining traction. She admitted that has also made #BabaeAko an easy target for trolls, but she echoed others in saying that the problem is rooted in something deeper than the medium.

“The culture, the kind of values, the system that we have, the patriarchal system – the double standard has always been there,” she said. “So yes, it has been magnified because of the tool, but nothing has changed. There should have been, we already have the Magna Carta of Women. We have done a lot, but suddenly we woke up one day and we’re sliding back.”

She said that the members of #BabaeAko are speaking up after realizing that far too many women withdraw out of fear on social media.

“You need to push back because you cannot have them monopolize this platform,” Bernardo said, referring to the misogynists online. “You have to think of ways to counter it with the proper guide and principles.”

Alindogan said the same thing. She confessed, “I realized now that you need to speak out strongly against this. You need to fight this head on. I used to just ignore online trolling and hate speech. I still mostly do that now, too, because I do not allow that to distract me from the work that I do. But when the situation calls for it, and when it affects others who do not deserve it and cannot defend themselves, I speak up.”

“Speaking for others is critical,” she said. “Being there and defending not just yourself, but showing solidarity with others is important. You can’t allow them to control that narrative. As women we need to set examples to the younger generations that we should not take these sitting down and that this culture should never be normalized.” – Rappler.com

To be concluded: 'Boys will be boys': Locker room talk and online harassment

CREDITS

- Graphics by Alyssa Arizabal

- Layout by Patrick Santos

This story was produced under the Southeast Asian Press Alliance 2018 Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by a grant from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.